Intertidal Body / Miscarriage Work

Writing about my practice

My writing and art practice endeavours to situate my personal experience within the wider ecological field, making a record of change in the body and in the ecological framework the body lives within.

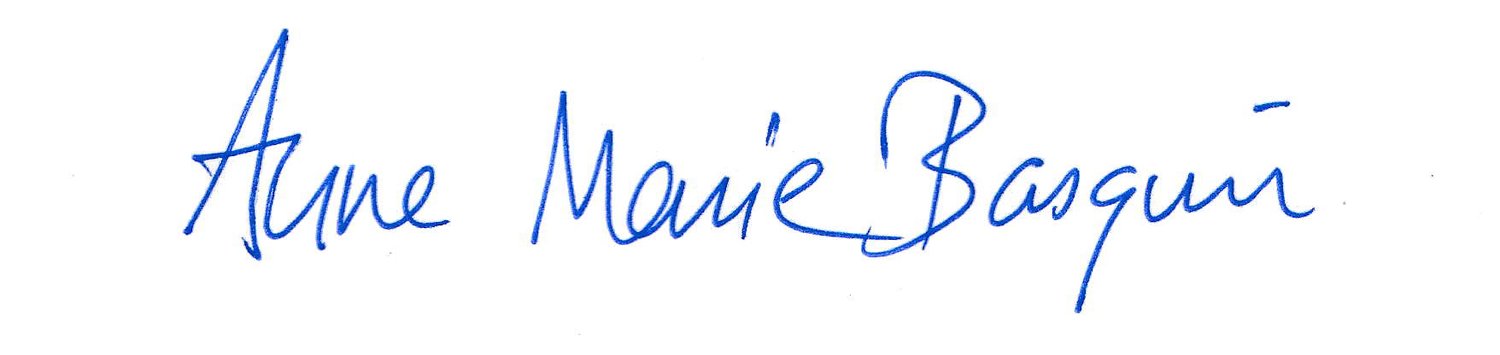

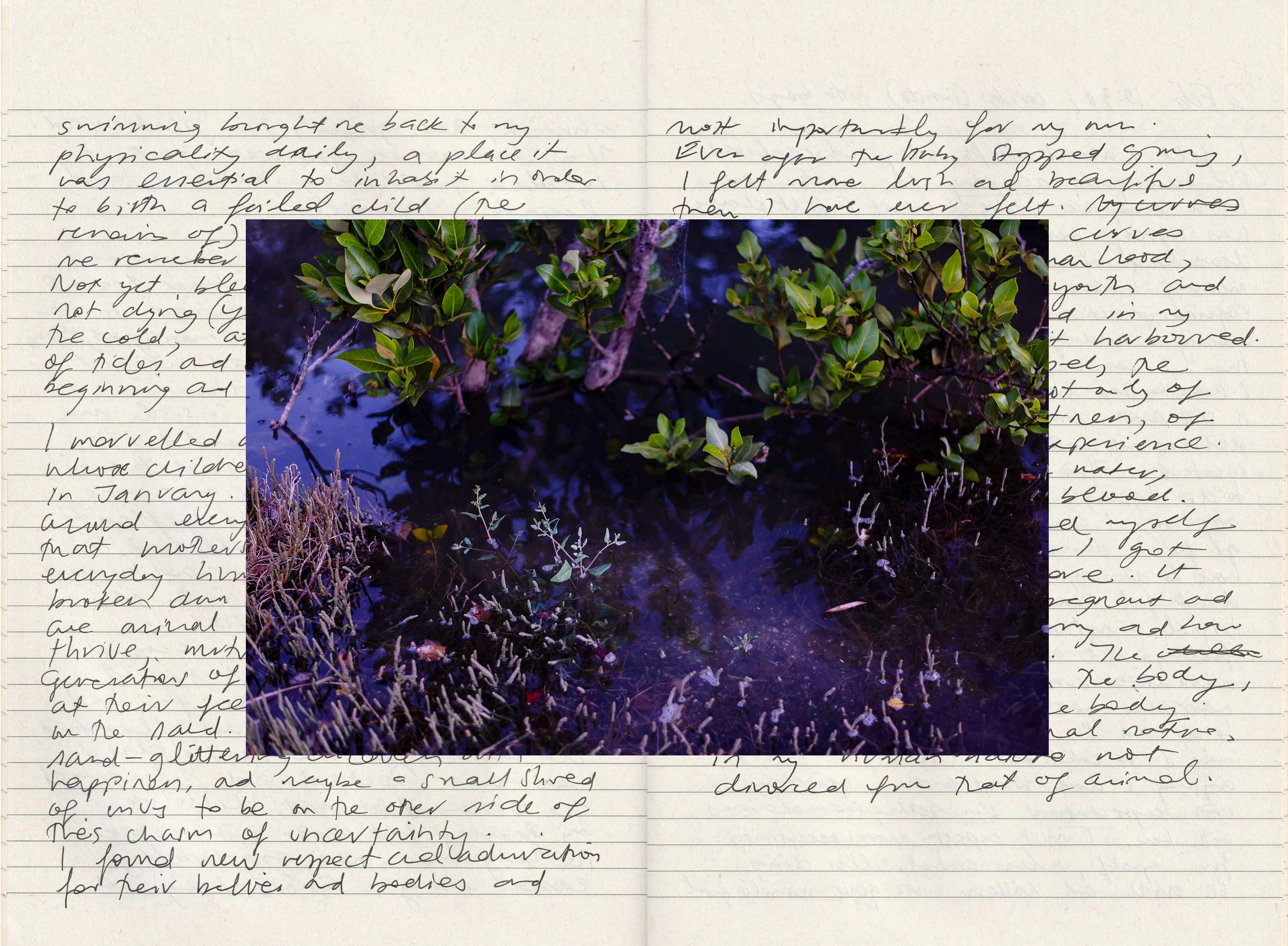

These photographs were taken when my partner and I went floundering a month after my second miscarriage. The pain of the second miscarriage made me animal. It was brutal but enriching and I was still reeling from the impact of it. Walking like a stilted bird through the shallows, water up to my shins, I felt animal, but not from pain. I stood in the water like a tall bird, peering in.

The ebb and flow of the mangroves soothed the hormones still ebbing from my body and the loss of the small failed body. I captured the magenta-hued world as night fell and I too felt magenta-hued, warmed by my very aliveness.

This work is an effort to capture the intricacies and intersections of miscarriage, subsistence living, and the coastal front lines of our changing ecosystems.

Excerpt from handwritten draft:

‘After the second scan, I recognised the hollow in my middle had turned to dead weight. The embryo in the second scan was smudged and grey, dissolved. The dead weight frightened me at first. To have a dead thing inside me felt dangerous. How would it come out? I was advised to wait.

My body started to feel more mine again, the life-force I’d gifted to the child slowly returned to me. I snorkelled and buoyed the dead weight along with me. The ocean was crucial in the formation of the second miscarriage’s narrative. It held me as I held the failed child. It rocked and floated and submerged me as the child too was rocked and submerged. The ocean did not dissolve my fears but eased them, as the baby too was gradually eased along.

Snorkelling and swimming brought me back to my physicality daily, a place it was essential to inhabit in order to birth a failed child (the remains of). The ocean helped me remember that I was animal: not yet bleeding, or, when bleeding, not dying (yet), sensitive to the cold, at the mercy of water, of tides and currents and epochs beginning and ending.

I marvelled at the mothers whose children swarmed the beach in January. How do we walk around every day just thinking that mothers are normal regular everyday humans? They have been broken down and remade, they are animal and yet they persist, thrive, nurture, grow the next generation of us. I wanted to bow at their feet, prostrate myself on the sand. I watched their sand-glittering children with happiness and maybe a small shred of envy to be on the other side of this chasm of uncertainty.

I found new respect and admiration for their bellies and bodies and most importantly for my own. Even after the baby stopped growing, I felt more lush and beautiful than I have ever felt. The prominence of my curves evidence of my womanhood, my humanhood, my youth and freshness. I delighted in my body despite what it harboured.

My body was it, the vessel, the sacred container, not only of new life but of witness, of ideas and art, of experience. It was how I felt the water, the sun and sand, the blood. It was how I defended myself from the sharks, how I got myself back into shore. It was how I became pregnant and how I would miscarry and how I waited in between. The world is run through the body, is first known by the body. I delighted in my animal nature, in my human nature, not divorced from that of animal.’

‘The pain makes me animal. Floundering makes me animal. Up to our shins in the mangroves from sunset to midnight I felt animal and not from pain, but because I stood in the water like a giant bird, peering in. Capturing the world as the light fades, I, too, felt magenta-hued, warmed by my very aliveness. Floundering in the dark is not unlike recurrent loss. The light illuminates only as far as it reaches. Flounder appear or don’t, we catch them or we don’t.

The time I don’t think of the loss expands. The whole time we’re floundering I don’t. Not thinking of the loss brings its own difficulty, returning to ‘normal’, to baseline, its own difficulty. Whatever I’m doing isn’t working, and to change, I don’t know where to begin. I lose sight of where I am, where I’ve been, easily clouded with old habits and goals, the old ways of doing things. This, (my) lower half submerged in water, in birth, brings me more alive. (Miscarriage is birth, it smells like birth, looks like birth, feels like birth, hurts like birth. Even the dead must be birthed, be borne. We can’t keep them inside us.)’

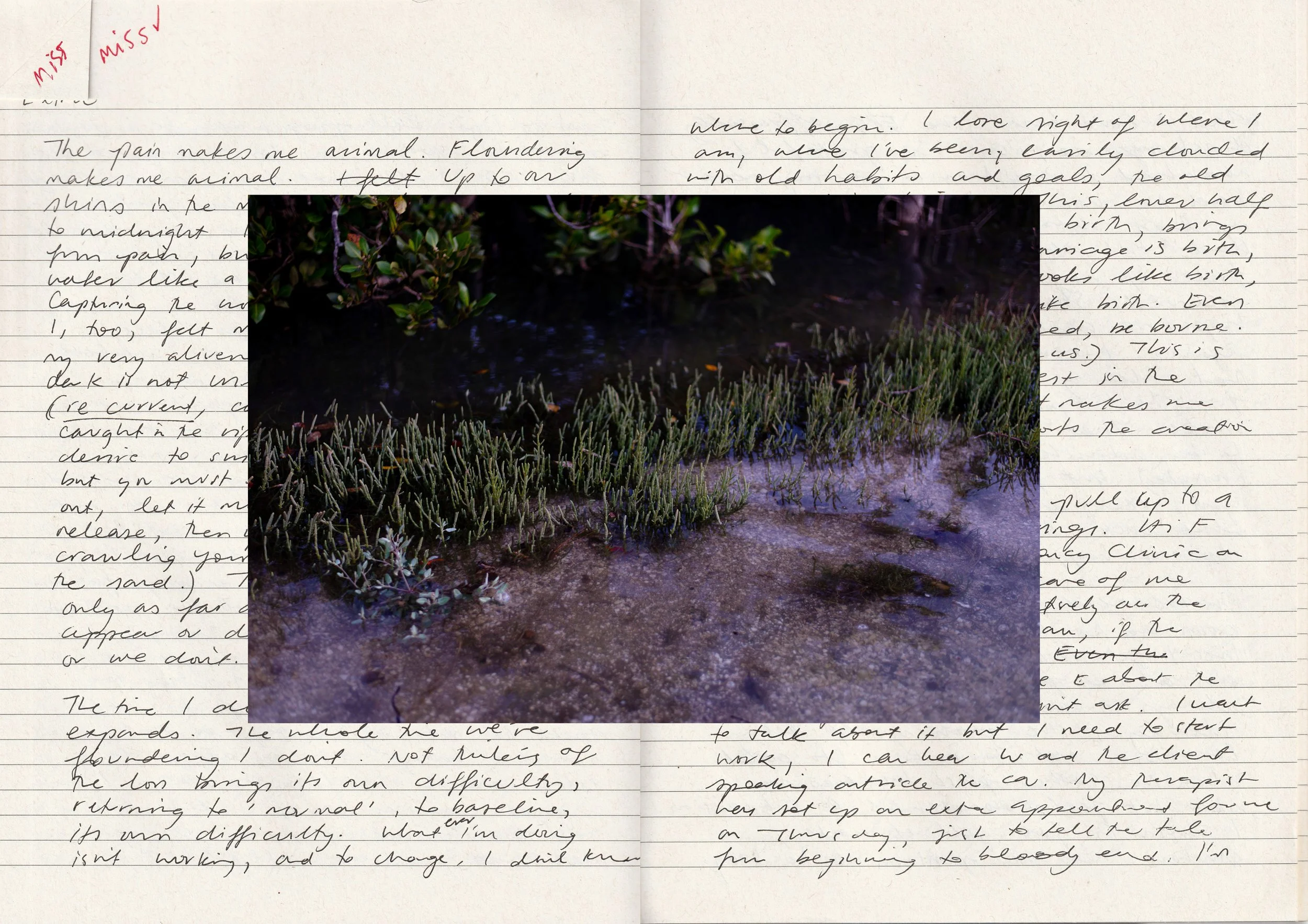

Notes Taken During a Miscarriage.

Index Card Front

‘the world shrinks to the size of your body, the room, the strength and duration of the pain

delirious

sweat, heat, dizziness, nausea

Animal

pain makes me animal

delirious

kneeling on the floor, head on a chair, bucket to my right.

Leaning over the sink

grimacing over the toilet’

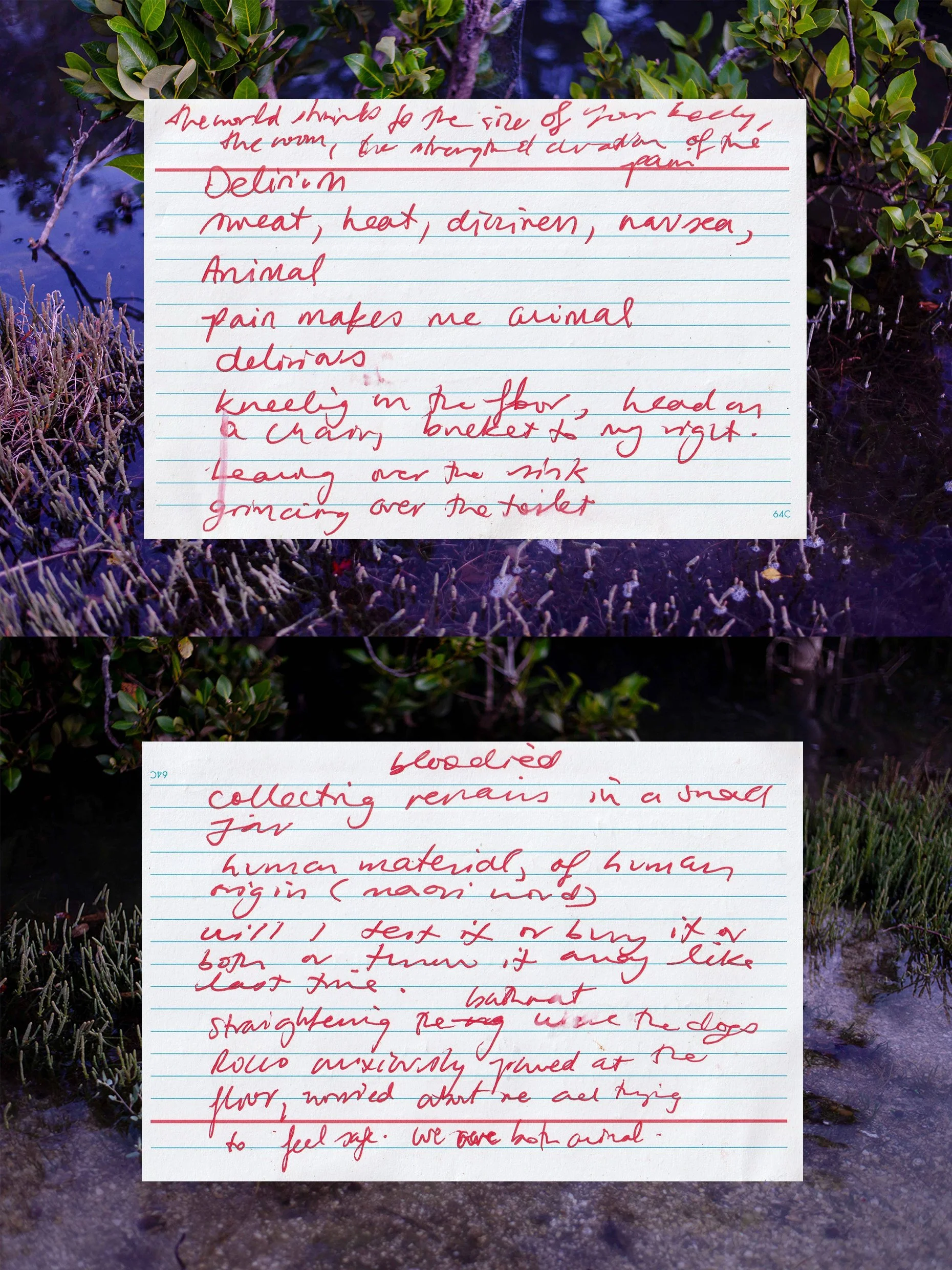

Index Card Back (I think I added these notes afterwards)

‘collecting bloodied remains in a small jar

human material, of human origin (maori word)

will I test it or bury it or both or throw it away like last time.

straightening the bath mat where the dogs

Rocco anxiously pawed at the floor, worried about me and trying to feel safe. We are both animal.’

Exposed kelp bed, Te Kohuroa Matheson Bay, 2025

A kelp bed sits exposed at low tide near the island at Te Kohuroa, its holdfasts, stipes, blades and bladders glint mustard-yellow in the evening sun. The falling tide pulls all the way out, turns, pours languidly back over the kelp’s yielding tendrils.

Behind the Work

I captured this photograph in the winter of 2024. The following spring, the Te Kohuroa Rewilding Initiative hired me as their assistant project coordinator to help deliver their summer pilot kelp reforestation programme at Te Kohuroa.

When the photography collective Women’s Work put out a call for submissions with the theme of (In)visible, I returned to the photographs of the exposed bed of kelp soaked in evening light. When I took this photograph, my body had not long undergone duress and loss, and the tide’s unending flowing in and ebbing out was soothing. The golden tones of the evening had lent the photograph a hopeful mood—and perhaps my body too—that matched the hope I felt as I dove down to the seafloor to gather kina. The sea and my body are greatly linked and after those losses I entered a covenant of caretaking with my body, at the same time I as I entered a covenant of caretaking with Te Kohuroa’s budding kelp. As I worked underwater, the concept behind the images I’d shot that winter began to coalesce. I chose the most impactful images, refined the concept and made my submission.

Artist Statement for Women’s Work 2025 (In)visible

This photograph was taken opposite the island at Te Kohuroa Matheson Bay, currently the site of community-led conservation run by the Te Kohuroa Rewilding Initiative, working towards kelp reforestation by removing an overabundance of kina.

Working within their female-led team, I can’t help but draw parallels between conservation and caretaking. Much of our labour, underwater or behind the scenes, is invisible, just as a clean home obscures the hours of work that go into keeping it that way. Arrowing down towards the seafloor to gather an armload of kina, I wonder how this work will be quantified at the surface.

This photograph peers through the ocean’s mirrored edge, to frame this ever-changing space at the intersection of observation and ecological dynamism, of women’s work and the caretaking of our ecosystems. This photograph aims to make our labours of caretaking visible.

I centred my artist statement around the idea of caretaking as a polite cover for speaking about miscarriage. I haven’t worked out how to speak directly about loss in these spaces (art and conservation) because it isn’t necessarily about loss, and certainly isn’t about these specific losses from my specific body, or not only about them, but about losses of all kinds, in all bodies, of all bodies, and in the larger planetary body.