Tsunami Dreams, EVACs & Election Tallies

This is an excerpt from a more comprehensive essay I'm working on. A little about my dad in this one, my great gran, I touch super briefly on politics and share a bit about miscarriage as it relates to Roe vs Wade being overturned. And tsunami dreams, more and more common the last few years. Happy reading xx

On the week of my birthday, I dream my mother and I are walking in a high paddock overlooking the sea at a kind of open-air market with L and K beside us. I point far below to where lines of swell rolling in from different directions cross, when a wave breaks backwards, in a kind of falling apart motion. Whatever had been holding this wave together — gravity, willpower, physics — broke, while a new set barrelled in behind it. A tremor starts in the far far distance, and in the dream world, we watch a tsunami break over a mountain range.

In 2024, my birthday falls on an election day in an election year, but because I live in Aotearoa New Zealand, Tuesday in this country is Monday in that one. I am allowed some grace before the tally of votes takes us where it will.

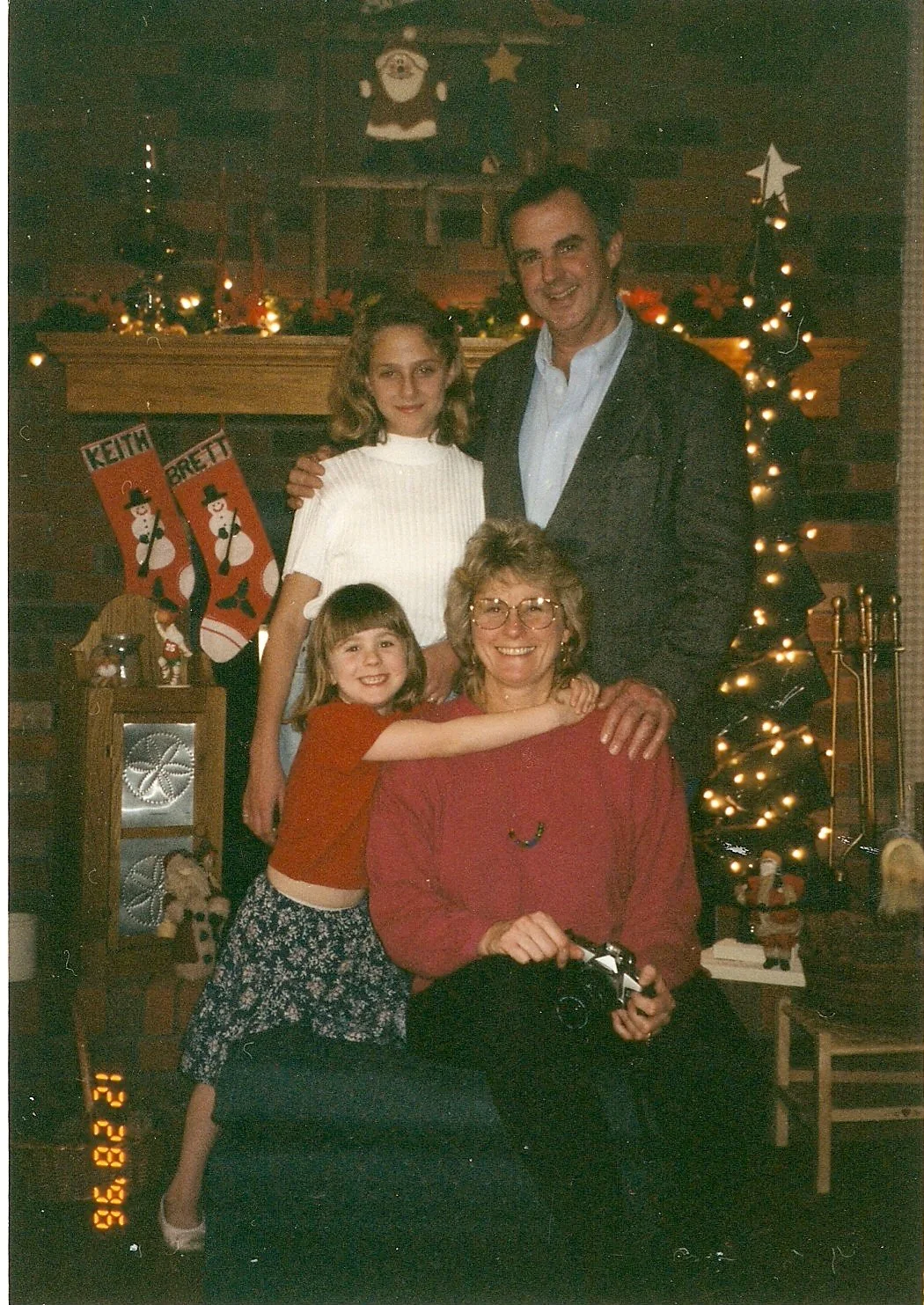

My father pre-emptively moved us out of the US in 1997. Pre-emptive exactly to what, I can’t say for sure. My father feared catastrophic climate events and potentialities — sea level rise, tsunamis, the return of the Western Interior Seaway, the west coast’s collapse into the Pacific — and the political personalities that could usher in a third world war, or some variation of it. He wasn’t wrong, only ahead of his time. Since we left in 1997, the United States government has financed more wars than can be comprehensively recounted here, most pressingly the war on Palestine; and a shift in the ideological balance of the Supreme Court has led to the overturning of Roe vs Wade.

My great grandmother Velma was born in 1901 and I had the dear pleasure of knowing her until her death in 2002. She was razor-sharp until the final year of her life when she reluctantly stopped driving and moved into a care facility. Long before all that, she believed in the right to choose. I was fourteen or fifteen when I heard her and my mother sharing their fears of returning to the days of back-alley abortions. My great grandmother was not a celebrated activist or political rebel — she raised two boys in rural Indiana, sold Tupperware, outlived her husband by forty years and lived to meet eight great grand children. I’m stunned that 123 years after her birth, we are still fighting over this basic right to choose, this basic right to safety.

Abortion bans across the US also restrict a woman’s access to D&Cs or evacs as they are termed in Aotearoa. In the last eighteen months, I underwent two miscarriages. The second time, I experienced a ‘missed miscarriage’ where the embryo dies but is not quickly let go of by the body. Four weeks after the embryo died, nothing had happened and I was scheduled for an evac, but the morning of the procedure the process started in my body naturally, and I elected to remain at home. Because every woman’s experience is different, the nurses I spoke to over the phone declined to describe what it could be like for me. I think they failed to sufficiently warn me of the dangers but I’m sure they were trying not to frighten me. I understood later that my first miscarriage was probably a chemical pregnancy, much like a very heavy period and very different to the second miscarriage. I did my best with L at home to keep an eye on how much I was bleeding while my vision blurred and swirled, and the pain made me animal. While I appreciate the experience for its growth opportunities — the transition from woman into veil into animal and back into woman again — I’m extremely grateful nothing went wrong. Next time, I would probably elect to have the procedure. Knowing that I have the choice here in Aotearoa makes the thought of trying to conceive again less intimidating.

Moving to Aotearoa New Zealand from Indiana and the Great Lakes region of the US was a decision that caused both heartbreak and happiness for each of us — fun for the whole family! Adventure for some, grief and the ever-increasing expense of flying back and forth for everyone. We are each greatly changed. Belonging remains the work of a lifetime. Nearly thirty years after the move, we thank my dad for his foresight and miss his company. He died nine years ago, on November 16th, 2015, not long after my thirtieth birthday. Moving to New Zealand was his legacy, the act that outlived him. His dream morphed into separate streams that live in his wife, daughters, and sons, anyone he loved and left.

That backward breaking wave — After he died, I felt that way, like the structures that had held me together were gone. But the structures weren’t gone, only changed.

As a young woman I learned to fear sex, pregnancy, childbirth, motherhood — that one thing always led to another. Becoming pregnant and losing the pregnancy felt like a backward breaking wave too, like the laws of physics letting me go. Harbouring the second failed embryo in my body for weeks, was similar again. So too was watching each due date on the calendar approach and pass, wondering if my genetic line is winding down to a halt with me. I hold my friends’ new infants in my arms, hold their hot little bodies close.

Watching the election results tally hard to the right, I felt the structure lose its hold. Despite the warnings, the pleading voices, this ideological shift in the governments of many of our nations is a door we are all going to have to pass through. We can look to history and to science fiction, but none of us can know exactly what we’ll find on the other side. Chaos? Anarchy? Freedom? Equality? More or less unconscionable wars? More or less judgement? More or less safety?

In dreams, I’m high up in a field, watching tsunamis break over mountain ranges, safe from earth-shattering events. This too is my dad’s legacy, built on the fields surrounding our farmhouse, far above the tsunami zone. My mom and sister and I extend his act, weave his dream into ours as best we can. It’s either that or run — but where would we run to?